A New Local Democracy for Scotland – Background Briefing

Introduction

This briefing provides background information on the Declaration launched on 9 September 2024. It highlights previous initiatives and ideas that have influenced the Declaration, but it is not a prescription or a list of proposals.

In 1973, Ted Heath reduced 400 Scottish councils to 53 districts and nine regions. In 1996, John Major reduced these to just 32 single-tier authorities – a level of centralisation he dared not impose on England where 10,480 parish and burgh councils survived with an average annual budget of £1 million, dwarfing Scotland’s 1,200 community councils with a miserable £400 per annum. As a result, Scotland’s 32 huge ‘local’ councils (average population of 170k compared to the EU average of just 10k) are distant organisations far removed from the communities they are meant to serve. Nevertheless, they are also victims of Holyrood diktat, as evidenced by the current row over a council tax freeze that other European governments could not enforce upon separate, self-governing tiers of democracy. It’s a mess that devolution was supposed to tackle but hasn’t.

Scottish Constitutional Convention

Twenty-five years after the establishment of the Scottish Parliament, the Declaration argues that while we should celebrate the many successes, we should also recognise that it has not created a genuine local democracy. The Scottish Constitutional Convention (SCC) envisaged devolution would not stop at the Scottish Parliament. They proposed that the Parliament would ‘secure and maintain a strong and effective system of local government’ that would ‘embody the principle of subsidiarity’ and the principles contained in the European Charter of Local Self Government.

‘The value of local government stems from three essential attributes: first, it provides for the dispersal of power both to bring the reality of government nearer to the people and also to prevent the concentration of power at the centre; second, participation, local government is government by local communities rather – as in the case of non-elected bodies – of local communities; and thirdly, responsiveness through which it contributes to meeting local needs by delivering services.’ (Scotland’s Parliament. Scotland’s Right. SCC report)

The subsequent Scotland Act 1998 had little to say about councils besides devolving powers to the Scottish Parliament. The relationship between these two tiers of government, both elected by ballot and with tax-raising powers, was not defined in statute.

Despite initiatives between COSLA and the Scottish Government, several commissions and numerous reports, we are no closer to achieving the principle of subsidiarity. In practice, powers have been stripped from councils and services such as police, fire, further education, and water have been centralised. The European Charter of Local Self-Government (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill was passed but blocked by the Supreme Court as outwith the powers of the Scottish Parliament. The latest UK monitoring report shows that Scotland falls short of the Charter; over-regulation narrows its scope for action, and there is significant dependence on national funding.

European Norms

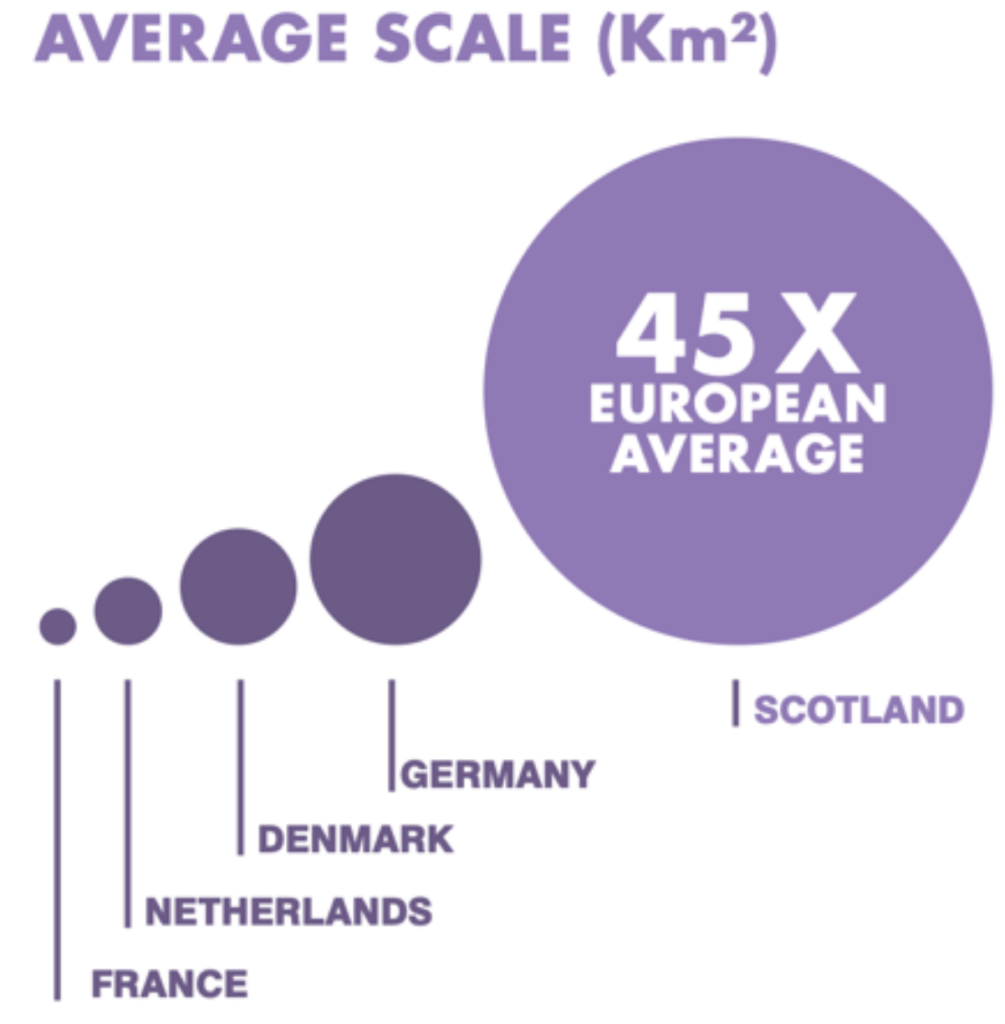

Scotland has some of the largest basic council units in the world, with an average population of 170,000, compared with a European norm of 10,000. Scotland also has the lowest number of elected members to population in Europe. England has an average of 2,814 people per councillor, Norway 572 and Denmark 2,216; the average councillor in Scotland has to look after 4,155 constituents.

Relationship with councils

The relationship between central and local government has often been fraught since devolution. In 2007, the Concordat set out the terms of a new relationship between the Scottish Government and councils based on mutual respect and partnership. It was supposed to reduce ring-fencing, a contentious issue with the previous Scottish Executive. However, problems continued (ringfencing of teacher numbers), and several councils withdrew from COSLA.

The latest iteration is the Verity House Agreement, which included commitments to give councils greater control over budgets and the expectation that services will be delivered locally unless agreed otherwise. Sadly, this was undermined within months when the Scottish Government announced a council tax freeze without any meaningful consultation.

There have been legislative and other changes since 1999, summarised here. These include the introduction of proportional representation and community planning. Despite local government being a devolved responsibility, the outgoing UK government has started to deal directly with councils by-passing the Scottish Government through its Levelling-Up Fund.

Reform proposals

A series of commissions and independent reports have highlighted the need to reform local democracy. While they sometimes offer different solutions, a common theme opposes centralisation. Many of these reports have cross-party and civil society support, pointing to a broad consensus on the principle of strengthening local democracy.

The Commission on Strengthening Local Democracy (2014) is a good starting point for understanding why local democracy matters. It concluded that ‘a radical transfer of power to communities is essential if we are to rebuild confidence in Scotland’s democracy and improve outcomes across the country.’ COSLA has followed this with supporting initiatives such as the Blueprint for Scottish Local Government (2020).

The Christie Commission on Public Service Reform recommended, ‘ A first key objective of reform should be to ensure that our public services are built around people and communities, their needs, aspirations, capacities and skills, and work to build up their autonomy and resilience.’

The Jimmy Reid Foundation has published several reports on these issues. The Silent Crisis: Failure and Revival in Local Democracy in Scotland (2012) argued that Scotland is the least democratic nation in Europe below the national level. Building Stronger Communities (2020) argued that the governance of public services in Scotland is one of the most centralised in Europe. It makes the case for the national government to focus on setting frameworks, leaving the delivery of services to local democratic control.

Our Scottish Future published a paper called Rewiring Scotland. While it ignores the revitalisation of grassroots democracy, it makes a credible case for reinstating something like Scotland’s old regional councils. However, it also supports directly elected regional mayors or provosts and other top-down initiatives introduced in England. We argue in the Declaration that none of these have produced a strong sense of local empowerment. Instead, they centralise power in a single individual, which could lead to unaccountable, authoritarian leadership and open the door to corruption.

Reform Scotland has a ‘Devolving Scotland’ forum that examines a range of ideas to help regenerate local government and set out a new vision for a decentralised Scotland. Their blog post on the Local Governance Review suggests practical proposals for local democratic reform that don’t require major structural reform.

This debate is not unique to Scotland. Power to the People?, a report from Compass and Unlock Democracy, assesses five proposals that could provide inspiration and guidance for an incoming government. In May 2024, former UK Government ministers David Lidington and John Denham made the case for giving England a statutory devolution framework.

Participatory initiatives

Polling for the ERS Democracy Max project found that 67% of Scots feel they have little or no influence over decisions that affect their local community, and 45% of people would like to have more influence over decisions that affect their communities. There have been several initiatives to improve citizen engagement and participatory practices in Scotland, which are analysed in this SPICe blog. These include Citizen Advisory Boards, Citizens’ Panels and Assemblies, Legislative Theatre, and other processes which facilitate conversation between communities and policymakers. What Works Scotland also published research exploring the developing role of key independent community sector organisations known as community anchors in building local democracy.

The Scottish Government, with COSLA, launched the Local Governance Review in 2018 to ensure Scotland’s diverse communities and different places have greater control and influence over decisions that affect them most. There was an interim report and a more recent Democracy Matters consultation. It is intended that this initiative will lead to legislation.

Council Finance

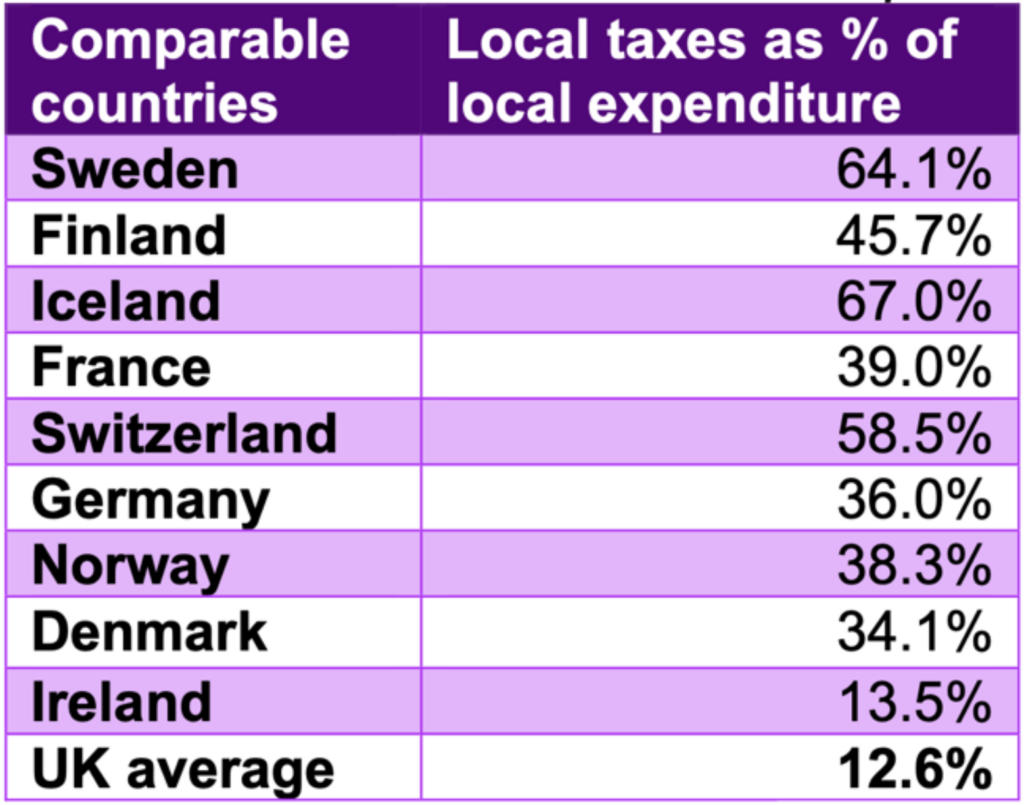

Successive administrations have avoided the reform of local government finance and the council tax (see SPICe Briefing). The Burt Report (2006) recommended moving towards 50:50 and identified a range of tax powers. The Commission on Strengthening Local Democracy (2014) asserted that change is required because Scotland’s councils have ‘become perhaps the least fiscally empowered in Europe’. They reminded us that 50 years ago, half of council income was generated locally. The Commission on Local Tax Reform (2015) concluded that ‘the present Council Tax system must end’. Following a 2018 consultation, the Scottish Government and COSLA supported ‘fiscal empowerment of democratic decision-makers to deliver locally identified priorities.’ The STUC and others have recently highlighted the need for reform and an immediate domestic rates revaluation, currently based on 1991 valuations.

Source: OECD Even a reformed council tax would still leave councils with little control over their finances. Council tax accounts for less than 20% of local government expenditure. The Burt Committee found that 23 out of 28 countries adopted multiple local taxes in its study. The Commission on Strengthening Local Democracy found the average for Europe is around 40%, but for countries where local governments have the equivalent responsibilities to Scotland, the average was between 50% and 60% of income raised locally. Local election turnout is generally significantly higher in countries with greater devolved taxation.

Conclusion

There is a strong case for further powers for the Scottish Parliament and Parliament being bolder with the powers it has. However, the Scottish Parliament could also give more power away to communities and power that can be democratically controlled locally. The aim is not to create more politicians; it is to get more people involved in the governance of our lives. Scotland has 32 councils, too big to be truly local and generally too small to be properly strategic. When local democracy is regarded by citizens as important in their lives, then those citizens also tend to be more engaged and active in building a strong community.