Building a Local Scotland: an economist’s view – Mike Danson

There is an incorrect presumption embedded into many government frameworks that, by definition, ‘big is beautiful’. The argument is then that that governments at all levels should embrace the need to realise the economies of scale offered by being parts of bigger entities. Best value regimes, public procurement rules, the Green Book (which the UK Treasury requires public bodies use to evaluate the benefits of public spending) and several other strategic and regulatory approaches to delivering public services and purchasing goods have protocols at their hearts which assume economies of scale necessarily must offer value for money to taxpayers and citizens. In turn, this promotes the notion that authorities and sub-national bodies should be merged or encouraged to collaborate to achieve discounts through bigger orders, as obviously suppliers will pass on the savings they can gain by producing bigger outputs.

In reality, rather than these anticipated benefits the result is often the imposition of uniformity, a lack of appreciation of local demands, and the erosion over time of competitors so that monopoly powers come to dominate. Dynamic changes in the relative powers of private sector suppliers and public bodies are seldom recognised in analyses of ‘best value’ strategies, while the losses to local economies and businesses are forgotten in the intervening years. And all these forces become cumulative, destroying local and regional industries and their established networks, linkages and skills.

uncritically expecting that bigger authorities are always better, with standardisation, loss of control and of the jobs, agency and decision-making capacities up the urban hierarchy to city-regions and distant corporations (see Community Land Scotland’s Scoping of the Classic Effects of Monopolies Within Concentrated Patterns of Rural Land Ownership). Centralisation and concentration of suppliers into fewer hands, far removed from the locality and the community diminishes democracy and destroys local enterprises, occupations and powers.

The interference and disruption of local production and service provision in favour of uniform high streets, destruction of local industrial specialisms and knowledge, and building reliance on external suppliers and people has progressively led to the underdevelopment of communities, regions and nations. Contrast the vibrant and resilient villages and communes in France, Italy and Norway, for example, with the standard shopping malls of the UK with the boarded up town centre and neighbourhood streets and closed libraries, town halls and swimming pools. These comparisons in the built environment cannot be separated from the loss of local powers and capacities, they are the natural corollary of the pursuit of bigger local authorities.

Further, a key performance indicator of the presumed benefits of larger local government units, and so of centralising and concentrating powers, is GDP (gross domestic product) and GDP per capita. This simplistic statistic underpins how the advantages of bigger orders from bigger suppliers distorts the government and governance of local and regional economies as it has become the measure of the economic value of a policy. ‘Cost savings’, and the related ‘increases in productivity’, are usually presented alongside the impact on GDP and its stable mate GVA (Gross Value Added), without consideration of what these terms actually mean and how they are constructed. Basically, the many issues with using GDP to gauge the health and performance of an economy have been analysed and discussed particularly in relation to outputs which conflict with sustainability, of the omission of the implied costs to people and the planet of pollutants. At the same time positive activities which do not enter into market transactions are not measured as contributing to GDP.

Although these issues have been explored at length, for small open economies, at the national level

but more tellingly for regions, districts and communities, there are significant shortcomings in using GDP as so much of the income generated – and so included in GDP – does not stay in the area, does not represent income to the local community and does not represent a direct benefit to their wellbeing. EIAs (economic or environmental impacts studies) of windfarm developments, for example, highlight the boost of local and regional GDP and GVA without admitting that much of this is effectively profit generated for multinational energy suppliers – whose shareholders seldom live in that rural community, rents for the rich landowners and a paltry ‘community benefit fund’ for some of those affected by the turbines. In other words, almost all the GDP/GVA flows well away from the glen or locality, and indeed from the Highlands or Scotland. That these flawed metrics are the mainstay of economic impact studies, and dominate decision-making over projects and developments, means that local voices are ignored in favour of the greater good, although the beneficiaries of that good are neither living in the areas nor subject to the negatives and costs excluded from GDP and GVA.

These are not esoteric arguments; they apply to many aspects of economic activities in our communities where local producers and suppliers have been driven out of the economy in the pursuit of economies of scale. Again, the loss of indigenous shops, surgeries, post offices, etc. to accommodate the penetration of multi-regional/national businesses into communities has been facilitated and encouraged by bigger local authorities themselves rationalised by all the accepted national economic and planning strategies; the long-term consequences of these interventions and resultant degradation of communities has been missing from evaluations of successive local government reorganisations.

How do these manufactured deserts of cleared producers, suppliers and facilities sit with other strategies for sustainable and resilient communities and environments: the circular economy, 20-minute neighbourhoods, community wealth-building, foundational economies, and their associated requirements? Can Building a Local Scotland be compatible with the aims of these strategies, and can a transition which embraces all these be just?

Well, in my articles ‘Progressive Consensus Versus Neoliberal Stagnation’ and ‘Building Back Better’, in the Scottish Left Review I noted how ‘there is a remarkable degree of consensus across Scotland, its Scottish Government Commissions, STUC, Commonweal, Business for Scotland, the Wellbeing Alliance, think tanks and visionaries as to how we should be planning for the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic’ and for implementing fundamental changes at all levels in Scotland.

There was, and remains, an opportunity to build ‘a better, greener, fairer Scotland’, as envisaged by many but that to ‘build back better’ there is a need to adopt the genuinely radical set of proposals being offered across this consensus. Localism, bottom-up, community-centred renewal is a common theme to all the strategies in the respective proposals, building on Scotland’s experiences and successes in applying European Structural Funds through partnership and recognising the advantages of collaboration at and across different levels of governance.

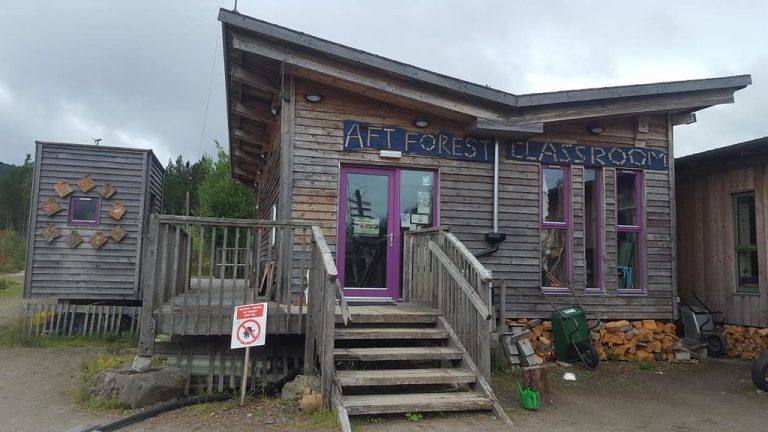

Consistent with these initiatives and visions, there are powerful lessons offered from the renewal of communities in the Highlands and Islands in recent years following transfer of ownership from monopoly owners to local people. These demonstrate what could be achieved by bringing authority, government and powers back home. Case studies (see Community Land Scotland’s ‘Evaluating Post-Monopoly Rural Land Ownership’) confirm how community land ownership has contributed to the sustainable development of a range of places in the Highlands and Islands and, in particular, how the economic and governance model of community land ownership addresses the pre buyout negative impacts of local monopoly land ownership. Relocalising powers and authority has allowed revolutions in the provision of enterprises and affordable housing, reinvigorating local cultures and networks, creating job and income opportunities so that populations and places are recovering and becoming sustainable. Environmental improvements are integral and essential to these developments, effectively delivering the slogan of Think Global, Act Local in practice.

Undoubtedly, there are services and other areas of life that do benefit from collaboration and delivery at the regional, national or international levels, and these can be designed and organised accordingly. But, principles of subsidiarity and localism should be the norm underpinning policy and practice from the community upwards, the local should not merely be places of amelioration and extraction.

In summary: concentration and centralisation of powers and authorities has facilitated the decline of many spaces and places through promoting monopolies in production and service provision, extracting incomes and surplus from communities and their environments to the advantage of shareholders and overseas governments and taxpayers. Flawed metrics such as GDP and GVA have been applied to obfuscate the realities behind the headlines, with systematic and self-sustaining degradation of natural and cultural heritage to feed the beast of monopoly capitalism. These trends and forces are not irreversible, and we have the analyses, policies and practices to support this as, for example, the studies of blossoming communities under land reform have shown. To complement the plans and visions outlined by different commissions and bodies for the strategic renewal and recovery of Scotland to build a better, greener, fairer Scotland, there also has to be genuinely local control and management over the nation’s resources and so return of local government to the island, town, village and city.

Mike Danson is Professor Emeritus of Enterprise Policy, Heriot-Watt University and co-director of the Scottish Centre for Island Studies. He publishes widely on community, rural and island development. Mike has served on the Scottish Government Just Transition Commission, the Tax Working Group of the Poverty and Inequality Commission and various governmental working groups.