Community and Resilience: The Keys to Powerful Local Government – Willie Sullivan

There are many reasons to seek really powerful, really participative local government in Scotland. Electoral Reform Society, Scotland published a longer pamphlet about this in 2022. Here we focus on what could well be the two most important reasons ; Community and Resilience.

Ours is a system that combines single, symmetrical units that seeks to treat everywhere the same. The different ways of doing this from across Europe suggests that it is possible to have small, powerful self-reliant communities, as well as authorities large enough to gives services that require larger areas and indeed that might do things that are at the moment done by the Scottish Government. This is not a debate between smaller or larger units under central government level in Scotland. Scotland needs both and many other things from its local governance to boot.

Big Problems

Its easy for even the smartest of people to fall into its ‘one way or the other way’ of doing things Humans are wired up to often see things as one thing or an other, to decide if something is good or bad, safe or risky, black or white.

This is helpful if we need to make a snap decision in a life-threatening situation and discernment is valuable, good choices are a good choice. But there is very little in life that is black or white. If you want to turn that instinct up to no 11 on the hypervigilance scale, add in technology that allows us to interact with faceless strangers all of the time and to have even our most out there opinions endorsed by a so called ‘ community’ on places like facebook.

These are ideal conditions for anxiety, division and populism. Throw in the complexities of global inequalities, the shrinking of the world by that same technology and mass migrations of people to escape war, poverty and climate disasters and you have some very big problems.

The history of technology’s negative impacts upon society has never been to uninvent things. Once the genies out of the bottle hes not going back in. But it is a history of adaption and mitigation, evolution even. First came the satanic mills then came the trade unions, city slums led to social housing we are seeing amazing technological responses to the threat of climate change but we also require significant social and political adaptions to the impacts of technology on our society and economy and the right wing populism that would exploit it. Adaptations that build resilience to the social, political and environmental shocks that have begun and will continue. This is not an argument for bad things, but it is an acknowledgement that they often happen.

Hope not Hate, a respected campaign and research body committed to opposing the far right recently published a report stating that to be resilient communities required ‘feelings of social connectedness’ and ‘agency and power’.

Step up community.

Communities are about human connection. Of course they don’t have to be about place but if the pandemic and zoom meetings taught us anything it was that proximity and sharing spaces together is really helpful in being truly connected. We also know that connection is vital for our good health and not only the deep friendships and family connections. The little chats in the street and the shared moans about the council seems to be very good for your wellbeing.

What really builds connections is allowing people the means to run the places where they live. Community is a product of shared interest, talking together, thinking together about what to do and then doing it together. It is mutual giving and receiving, the basis for trust and could be the basis for the best lives and the best places.

Human connection allowed and encouraged by good community organisation is essential in helping to make the conditions that lead to healthy and happy people. There is little doubt that the creation of a modern Scotland capable of being foundational to many better lives depends on the ability to create a system of government that prioritises human connection and community. This must start with the most local structures of the state.

The Resilience of a web

A spiders web is a marvel of design. The remarkable strength of its almost invisible structure is due to the fact that if one threads break others take up the strain. It is the multitude of connections and mutual supporting parts that create gram for gram the living worlds strongest structure.

A community is a web of human relationships. The more trust and interdependency, the stronger they are. They are the opposite of division and polarisation. While communities do form naturally, just like families they can be more or less healthy. They can be built by people working to hand in hand to make good places to live. To do this they require power. There are many complex theories of power but Jane McAlevey, the US Trade Union organiser and later theorist and academic said ‘Power is the ability to stop bad things happening to your community and to make good things happen’.

How to build it

Local government is a large and complex organism, some parts of it work very hard to support communities but it sometimes works against itself. The structures and systems of large organisations can end up serving the organisation or others more than the community.

Despite the best efforts of the founders of the parliament, Scotland inherited much genetic constitutional code from the United Kingdom. We are largely a centralised state run from the top down. We suggest that the more centralised and hierarchical things are the more dis-empowered people and communities are. Those that support limited or no change should be challenged to present arguments as to why this is not true or else why dis-empowerment of communities is a price worth paying for other benefits.

There at times when this may be the case. Perhaps strategic infrastructure is vital for the good of the whole population and this may mean compromise from a local community. However the full explanation and involvement of that community in the decision making process is vital if they are not to become resentful, alienated and potentially damaged.

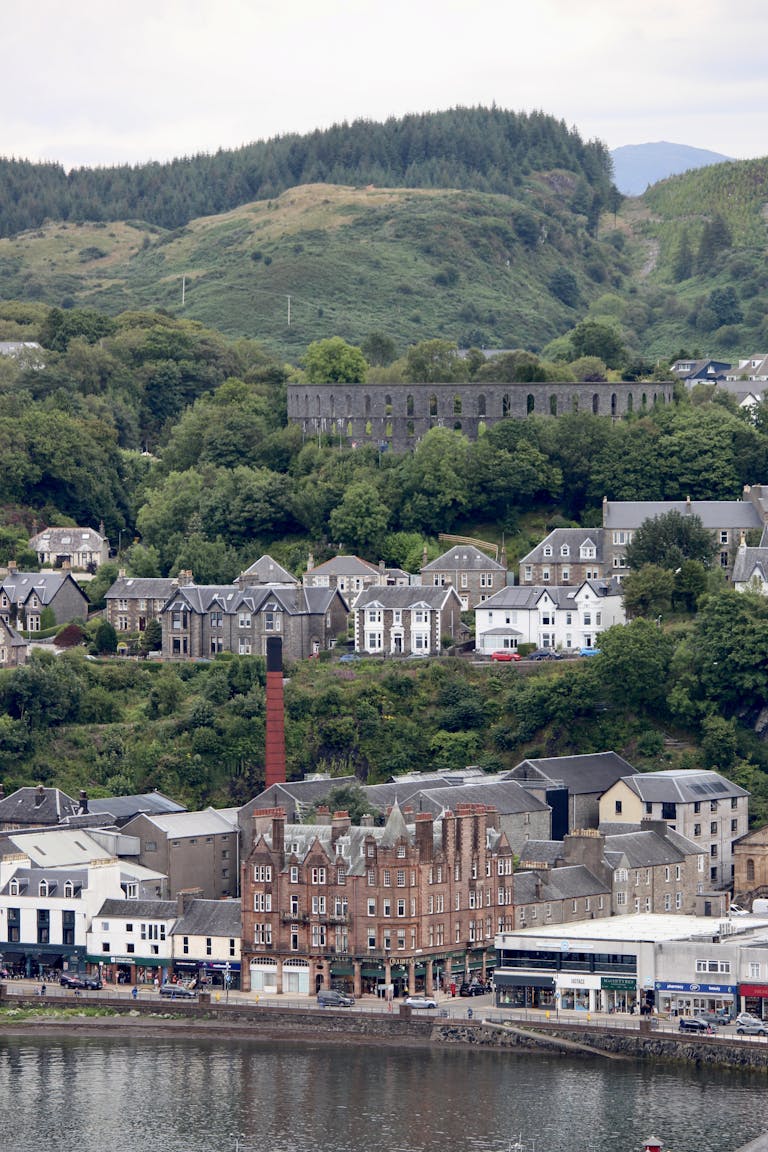

Cities, towns and villages were for the most part created by their inhabitants, later supported by a central state, but they were made locally. In one of his last posts, the late David Donnison, one of the leading activist scholars in this area, noted that ‘most important policy innovations of the past – the building of the first district general hospitals and subsidised housing, the creation of comprehensive schools, the invention of foster care for children previously consigned to institutions of various kinds – all began in local government, usually in the teeth of opposition from central authorities’. Living as community and in a place is a very natural thing for humans to do. The question for the Scottish Government, COSLA and the parliament should be – does the way we currently organise our local government maximise our ability to support healthy, open and inclusive communities to grow and in what ways is it antagonistic towards that aim?

Citizen-led organising and responses to Covid and the lockdowns have been noted and applauded by many in government. There was a fantastic citizen-led response in food deliveries and other forms of mutual aid. In meetings with some of the organisers of foodbanks and community kitchens that came about in response to the pandemic, it was clear that some of this was done largely unsupported by local authorities, but much was done collaboratively.

Further information from ERS polling suggested that this energy of community activity is a very large potential resource.

Over four in ten respondents (44%) said they would be willing to give up their free time to help their local council make decisions on issues that affect their community.

Only a third of respondents (33%) said they would not, while around a fifth (23%) were unsure.

Nine in 10 (91%) of those who would be willing to get involved, said they’d be willing to give up two or more days per month to help their local council make decisions on local services. Three in five (58%) would be willing to help out for three or more days. The average number of days respondents were willing to give up to help their local community was 3.4 days. 43% of people would be willing to give up four or more days per month.

This suggests that there may be more willingness to engage than is often suggested. People do want the council to empty bins, keep the streets clean and much else without too much hassle but they also want to be involved in planning and shaping the future of the place they live and they also want to be involved when these things aren’t working well (which is not infrequent) and to help find ways to make them work better. At the very least, people ought to have the opportunity to engage in this way. Many more people are very interested and invested in their local place and would like to find ways to engage with its governance than our institutions currently allow

Too far away

Proximity builds trust and legitimacy. Moving power and representation closer to where most people live their lives can be used as a way to increase transparency – as long as there are rights to information and proper systems of scrutiny.

More local power does allow people to feel more connected with it. People went to school with their representatives, work beside them or their family and know people that know them. If citizens assemble and other mini publics are built into the system, the more people see people like them involved in making the decisions for the places where they live. If representatives are close to people it is also easier to spot when things go wrong. It makes accountability much easier and can use the constraints and incentives of being part of that local community to ensure people act as their best selves.

Many would say this is true of local councillors right now and it certainly is in some cases, although the size of current wards hardly encourages proximity. There is something in the nature of joining a party and seeking an election that also makes you different. We should aim to make it a much more normal thing to be a community representative. In some countries it as seen as a community duty, something that many people take a turn at. This might be helped by smaller units and wards creating less onerous levels of representation. Representing a few hundred people is easier than being a councillor for four thousand.

Democracy that connects not divides

We know that building citizens into the running of local places can increase trust and connection and therefore resilience. A citizens assembly would be a highly representative group of the local community, scientifically selected using sortition so that all relevant groups are represented. They would be paid and facilitated to ensure that people from largely excluded backgrounds could take part. They are asked to use their experience of living and knowing the local place to consider evidence and learning and to decide together what is desirable and possible for that place.

These are not a brief committee meeting, but in-depth discussions held over perhaps several blocks of two-day sessions. They allow people to understand each other, while not always agreeing, and effectively counter the divisive nature of party and council chamber politics and the impact of social media polarisation. They tend to produce a set of proposals that citizens feel they own and are proud of, and the assembly see themselves as champions of.

The most important thing to do?

Human beings can be frightened, selfish, greedy, deceitful and cruel, but they can also be courageous, selfless, generous, honest and kind.

If we are interested in shaping our society it seems pretty self evident that we really want to create conditions where its easier to be the latter rather than the former. That’s not to say that we will get rid of those darker behaviours, just as we want entirely banish them from ourselves but to turn up love and turn down fear just seems like something all of us should be invested in.

Is this really a possible goal for local governance ? Well if local governance is about how we organise and run our communities it very well may be the best way to do it.

Willie Sullivan is the Senior Director for campaigns and Scotland at the Electoral Reform Society. He is a creative campaigner designing and leading campaigns , interventions and policy ideas towards trans-formative outcomes. He is particularly interested in reform of the institutions of government and democracy and in democratic innovations such as citizens led democracy.