We can ‘right-size’ democracy in Scotland – Lesley Riddoch

Something special happened in 2022.

A Scottish election with the lowest ever number of candidates, a turnout of just 44.8%, the lowest in northern Europe and a high number of wards where there was no election because candidate numbers precisely matched the available seats.

But there was very little fuss or recrimination because these were local elections.

And Scotland just doesn’t do genuinely local government.

Instead, it has enormous, regional and even country-sized councils – our islands excepted – the largest ‘local’ councils in the developed world. And whilst that scale may work in cities, it’s killing town, rural, island and village Scotland, by failing to harness the talents and energies of local people.

It is time to right-size our democracy

I’d guess the thankless nature of a councillor’s job deters activists from standing. Instead, energies are poured into community buyouts where people can exert meaningful control instead of losing income, valuable time and the will to live by traipsing back and forth to ‘local’ council HQs a day’s drive or several ferries away.

So, when Scots once again produced the lowest turnout for local elections in northern Europe it wasn’t evidence of apathy or hostility to genuinely local government.

It was a plea for change – that fell on deaf ears.

Of course, we have had some big constitutional fish to fry over the last decade. So, it’s impressive that key figures from both sides of the constitutional divide are working together on this project to decentralise Scotland.

We understand voters and the media may take some persuading that something as apparently administrative, low-key and couthy as local government reform could be transformational.

And yet, speaking as the director of the policy group Nordic Horizons, this is the biggest single structural difference with our nearest neighbours. Norway, Iceland, Sweden, Denmark, Finland are not just small, independent countries, they are rooted in hyper-powerful, vibrant local democracy.

The French Sun King Louis XIV famously said, Le’etat – c’est moi.

But in these very successful Nordic countries, the state isn’t one unelected monarch or even a single elected parliament with nationally controlled systems. The state is a composite of all its many, many parts. Each national system – like energy – is the product of hundreds of individual hydro dams owned by local municipalities – which has funded the country’s excellent infrastructure, even in the most remote areas. And income tax isn’t the sole preserve of Oslo, Stockholm, Helsinki, Copenhagen and Reykjavik.

In Sweden it’s paid completely to local councils by the average tax payer, with central government funded by higher rate taxpayers and corporation taxes. Elsewhere there’s an agreed formula that send roughly 20% of income tax directly to councils as large as 600k in Oslo or just 80 in one of the smallest councils on the Faroe Islands. That certainty of income lets pint-sized councils move ahead with the community-saving investments that larger councils would squabble over for years and finally procure at several times the cost of locally-run projects using volunteer talent and local sweat labour.

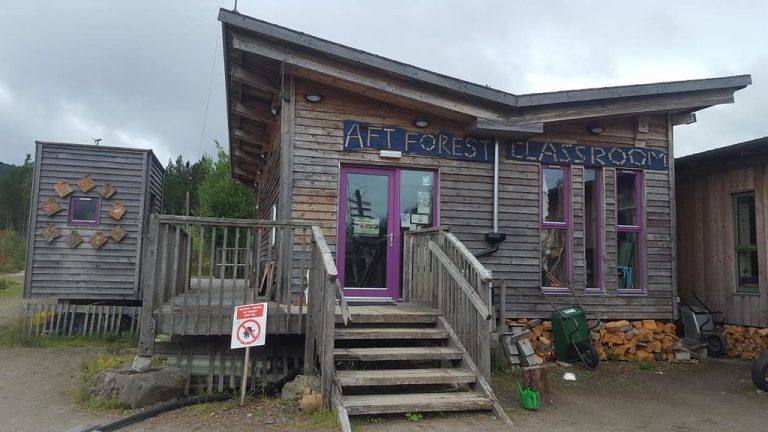

That’s how the Faroese council of Vagur built a 50m swimming pool for a quarter of the ‘official’ cost. Vagur has just 1377 people – probably the smallest town with an Olympic standard pool in the world. But – like many remote, rural villages and towns across the North Atlantic – it was fighting for its life, as traditional industries and fishing jobs decline. Vagur’s former Mayor Dennis Holm says the town believed it could coax youngsters back after university education elsewhere if they created good memories of childhood – full of sports, activity and positivity.

And that was possible because Vagur is not run from anywhere else and easily harnesses the talents of its people.

How do mini councils manage their service commitments?

Norway’s Local Government Minister Ole Narud told a 2022 Nordic Horizons event that small councils double up portfolios, cooperate with neighbours and hire Education Directors who are also part-time teachers – not a clutch of highly-paid officials. Because home lies a walk not a day’s drive away, council meetings are in the evening, so councillors aren’t paid because day-jobs can continue. Poorer councils are supported by transfers from richer neighbours and central government and cooperate with neighbours in a way private outsourcing companies cannot, challenging big spending projects at the start with different outlooks in a way large ‘monopoly’ councils do not.

According to Norway’s Audit Office, these jointly managed projects by several small councils are the best delivered projects in the country.

In short, Scotland would have looked and felt very different if our democracy had been equally local, democratic and powerful for the last century.

All political parties – even the Tories – agree power must be moved out of Holyrood. Of course, that’s easier said than done and there will be nervousness about change. But done wholeheartedly – with guidance from our very willing Nordic neighbours, we can ‘right-size’ democracy in Scotland.

And that would be fairly seismic.

Lesley Riddoch is Director of Nordic Horizons, co-producer of 5 Nordic films and completed a PhD comparing Scotland and Norway in 2021. Columnist at The National – former Scotswoman editor, Isle of Eigg Trustee, and now a journalist, podcaster, author of Blossom & Thrive.